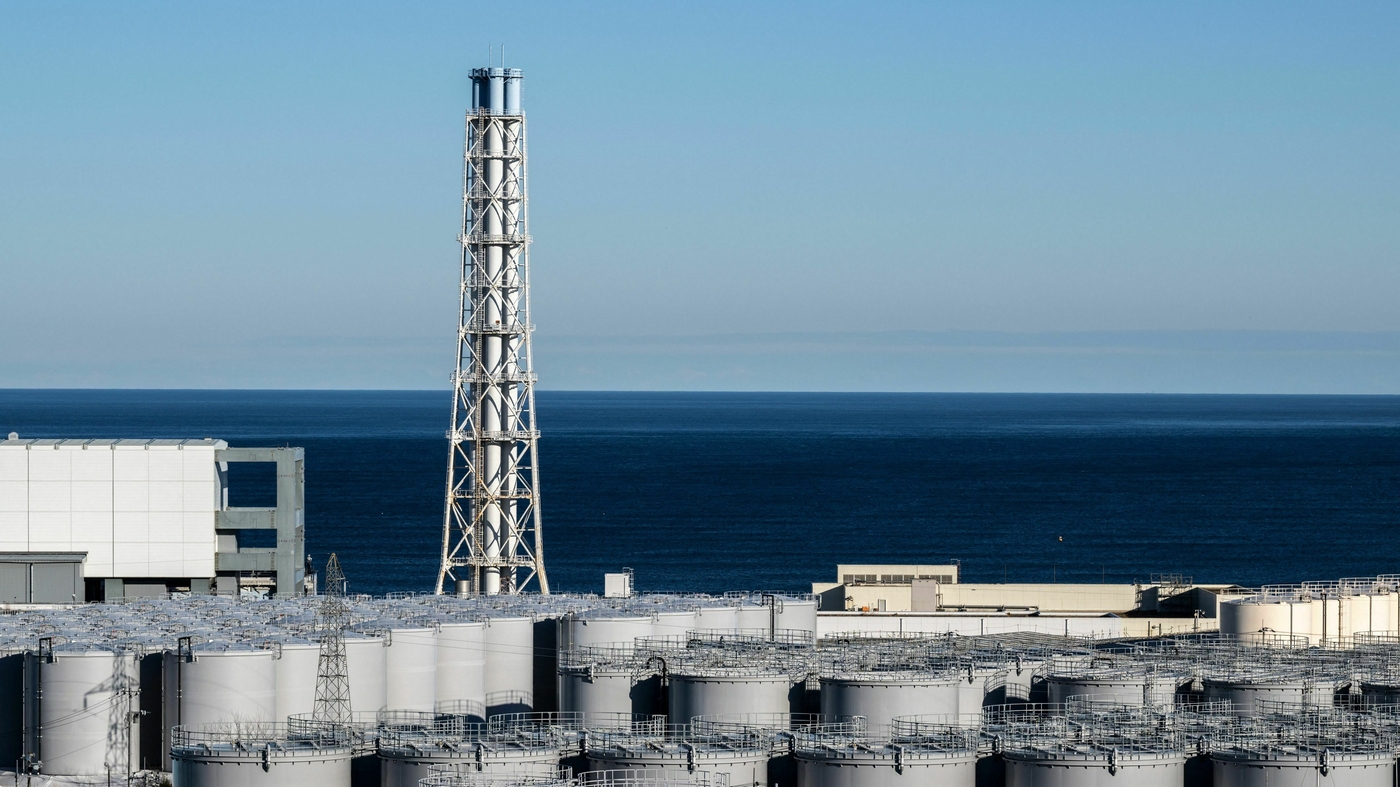

The water at the nuclear power plant in Japan will have treated radioactive water

by admin

The First Release of Treated Water and the Risk of Exposure to Radioactive Isotopes in Japan’s Ocean Water

The first release of treated water is expected to last 17 days. Tepco and the Japan’s fisheries agency said they will monitor the ocean water for radioactive levels, as well as the IAEA who said it would also supervise the process.

“The idea of deliberately discharging hazardous substances into the environment, into the ocean is repugnant,” Lyman says. “But unfortunately, if you do look at it from the technical perspective, it’s hard to argue that the impacts of this discharge would be worse than those that are occurring at nuclear power plants that are operating worldwide.”

The government has been working on a complex filtration system that removes most of the radioactive isotopes from the water. Known as the Advanced Liquid Processing System (or ALPS, for short), it can remove several different radioactive contaminants from the water.

The Japanese government believes that there is no reason why tritium shouldn’t be as bad as other radioactive material at the site. Its radioactive decay is relatively weak, and because it’s part of water, it actually moves through biological organisms rather quickly. And its half-life is twelve years, so unlike elements such as uranium 235, which has a half life of 700 million years, it won’t be in the environment all that long.

The International Atomic Energy Agency has peer-reviewed this plan and believe it is consistent with international safety standards. The IAEA also plans to conduct independent monitoring to make sure that the discharge is done safely.

“The risk is really, really, really low. And I would call it not a risk at all,” says Jim Smith, a professor of environmental science at the University of Portsmouth. He has studied radioactivity in water after nuclear accidents, including at Chernobyl.

Smith thinks that the effects of the release of radiation won’t be significant, in his opinion, if it is done properly.

But not everyone agrees that discharging the water is the best option. The senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute thinks that it would have been better if the contaminated water had been kept on land. Mixed it into concrete to make it stick to it was one option.

“Nearshore in Japan could be affected in the long term because of accumulation of non-tritium forms of radioactivity,” he says. That could hurt the fish population in the area.

The Pacific Islands Forum, which also includes the Marshall Islands and Tahiti, is worried about Japan’s decision. He notes that many of the countries were subjected to nuclear tests during the Cold War. “They cannot return to islands because of legacy contamination,” Buesseler says.

He says that they are suffering from climate change more than the rest of the world. They say Japan’s release into the Pacific is just one insult.

The plan to release wastewater into the sea has provoked tension between China and South Korea, as well as anxiety at home. The Chinese government has criticized the plan as unsafe; in South Korea, the administration of President Yoon Suk Yeol supports Japan’s efforts, but opposition lawmakers have castigated the move as a potential threat to humans. Fishermen’s unions in Japan worry that public anxiety about the safety of the water could affect their livelihoods.

The first release of treated water and the risk of exposure to radioactive isotopes in Japan’s ocean water is expected to last 17 days. The first release of treated water is expected to last 17 days. The government has been working on a complex filtration system that removes most of the radioactive isotopes from the water.