Cells inside a bag are capable of growing new cells inside people

by admin

Using stem cells to generate personalized organelles for the treatment of a person with liver failure and monitoring it for vaccinations: an application in liver transplantation

If the liver trial is successful, Gouon-Evans says, it would be worth investigating whether a person’s own stem cells could be used to generate the cells that seed the lymph nodes. She says the technique could create personalized cells that dont need immunosuppressive drugs.

Many people on the transplant list in the United States will wait a long time for a new organ. Because of other health problems, those who don’t qualify for a transplant because they need a new one aren’t included.

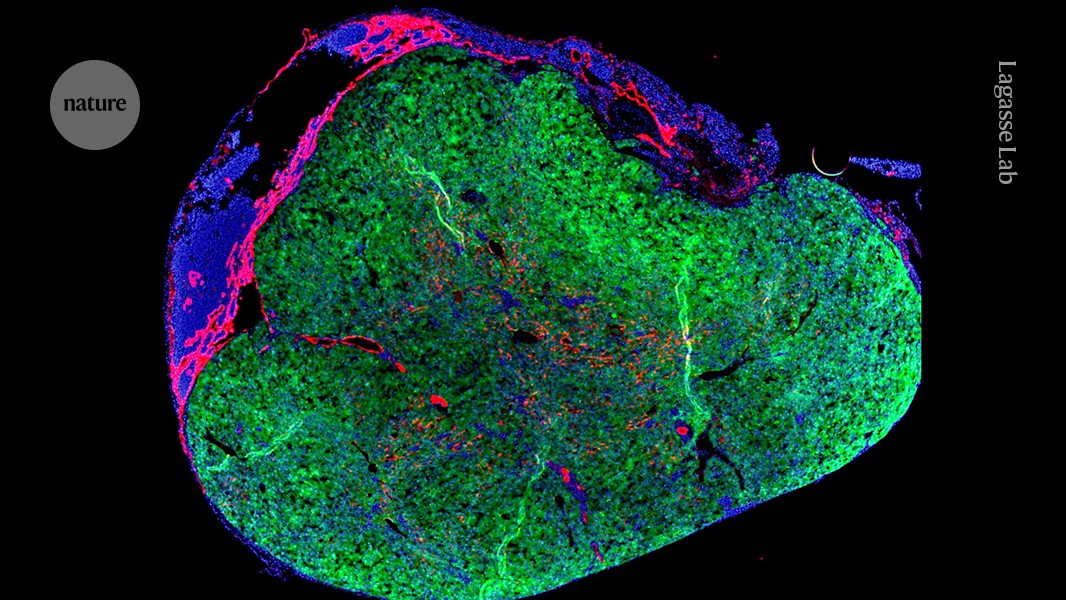

The approach is different because the researchers injected a donor’s cells into the abdomen of a person with liver failure. The idea is that during several months, the cells will create a structure that will be able tofilter blood from the person’s illness.

“It’s a very bold and incredibly innovative idea,” says Valerie Gouon-Evans, a liver-regeneration specialist at Boston University in Massachusetts, who is not involved with the company.

The person who received the treatment on March 25 has recuperated well, and been discharged from the clinic, states Michael Hufford, the chief executive of the company. But physicians will need to closely monitor them for infection because the person needs to take immunosuppressive drugs so that their body doesn’t reject the donor cells, says Stuart Forbes, a hepatologist at the University of Edinburgh, UK, who is not affiliated with LyGenesis.

The End of Liver Disease: The Role of Mini-Living Organs in Surgical Effectiveness and Post-Transplantation Safety

Each year 50,000 people in the US are killed by liver disease. In the end stage of the disease, scar tissue in the organ can cause infections or cause cancer if it doesn’t get rid of toxic substances in the blood.

Hufford thinks that there isn’t reason to think that the organs won’t grow indefinitely. The mini organs rely on chemical distress signals from the failing liver to grow; once the new organs have stabilized blood filtering, they will stop growing because that distress signal disappears, he says. He adds that it is not certain how large the mini-livers will become in humans.

The company hopes to enroll 12 people in the phase II trial by mid-2025 and publish their results over the course of a year. The trial, which was approved by US regulators in 2020, will not only measure participant safety, survival time and quality of life post-treatment, but will also help to establish the ideal number of mini livers to stabilize someone’s health. The aim of the trial is to find out if the extra organs can boost the procedure’s success rate.

Forbes has formed his own company to address liver disease using genetically modified immune cells that cause repair, but he says mini livers don’t cure the problem. One of the most serious of these is portal hypertension, in which the build-up of scar tissue compresses blood vessels in the liver and can cause internal bleeding.

US-based LyGenesis has developed an experimental method of using stem cells to produce personalised liver cells for people with liver failure. The researchers injected the stem cells into the abdomen of a person with liver failure and then monitored them for infection. LyGenesis claims to be the first company to perform such a test in the US.