What is at stake in the Supreme Court case?

by admin

The Case for Prohibiting Access to Abortion in the U.S., and Implications for the Health of Contraint Therapies

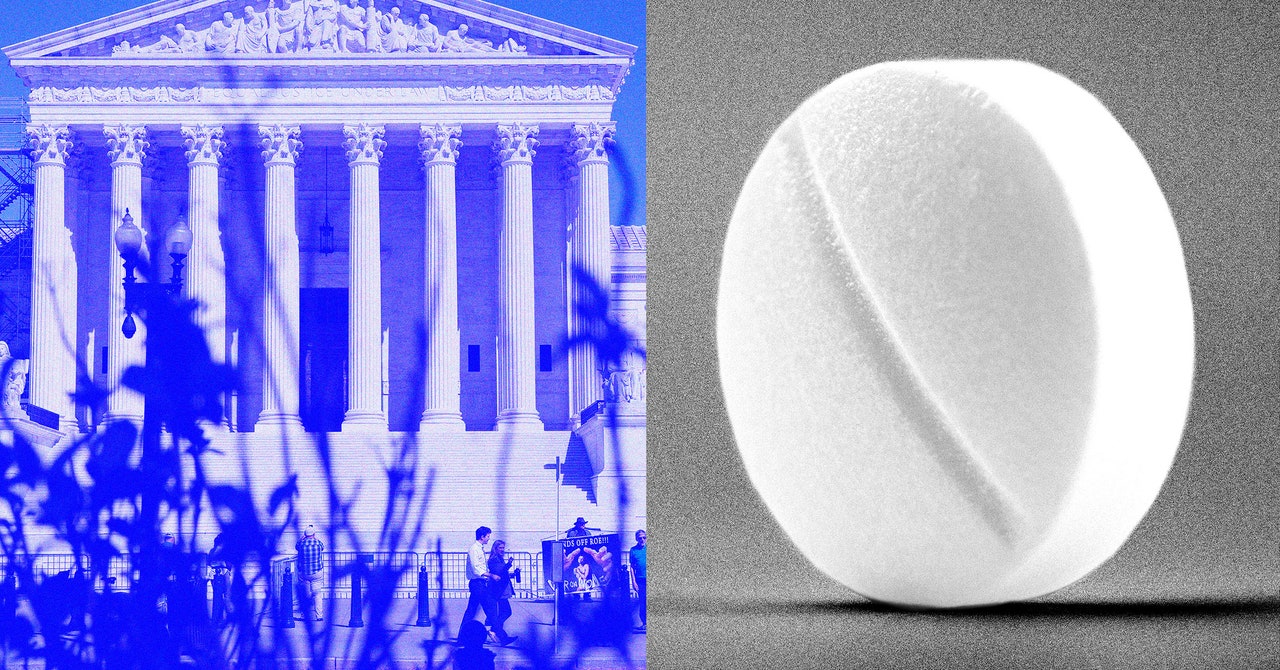

If the justices side with the antiabortion activists, it will lead to the end of abortion access in the country. Any judge that overturns the FDA approval of any drug would be free to reverse it, especially controversial drugs like HIV drugs and hormonal birth control. It could also have a chilling effect on the development of new drugs, making companies wary of investing research into medicines that could later be pulled from the market.

Drug companies could use the case to challenge FDA approval of a competitor, argued the former FDA Commissioners in the amicus brief. They write, “organizations representing patients who experience rare adverse events could challenge FDA’s risk-benefit analyses and try to bars access to safe and effective remedies for others who need them.”

It is a high-stakes case, because not only does it affect abortion and reproductive health care but also the authority of federal agencies and the drug industry. Here is a summary of what’s at stake.

The popularity of pills is increasing, and they are the leading abortion method. More than six in 10 abortions in 2023 were carried out via medication, according to new data from the Guttmacher Institute. Virtual clinics that send abortion pills by mail have become popular because of the relaxed rules around telehealth during the Covid-19 pandemic. Hey Jane, a prominent provider of telemedicine, saw demand increase 73 percent in the last five years. It recorded another 28 percent spike comparing data from January 2023 to January 2024.

“We use this medication in lots of different ways and for lots of different care,” including for miscarriage and pregnancy loss, says Dr. Jamila Perritt, an OB-GYN in Washington D.C. who’s the President of Physicians for Reproductive Health. “If this medication is restricted or banned completely, no one will be able to get access to it with any ease,” she says.

Under the new rules, which are expected to be in place before the end of the year, it would only be allowed until seven weeks into a pregnant woman’s life. The medication can be used as late as 12 weeks.

According to the CDC, half of medication abortions happen after seven weeks, even though it might not seem like much. The earliest someone could find out that they’re pregnant is four weeks, which is why the COO of carafem explains that.

A seven-week limit gives people three weeks, at most, “to get a positive pregnancy test, determine what option is best for them, potentially involve people that they care about in their lives, find an appointment, look at potential assistance for the finances of it, and then actually go and get the medication and use it,” she says. “That’s a rapid turnaround.”

Can the Comstock Act be reinvented as an abortion ban? Michelle Banks, the mother of two miscarriage cases, explains why she takes mifepristone

Mifepristone allowed the woman to get through many years of family planning challenges, which involved a lot of miscarriages.

For instance, Michelle Brown told NPR that after she learned she was miscarrying, she was nervous she would start bleeding on her long commute to work in Louisiana, where there was no safe place to pull over. Taking mifepristone allowed her to plan ahead so she could be comfortable at home with her then-fiancé.

In the nearly two years since the Supreme Court overturned Roe, states have moved in two opposing directions – about half of states ban or seriously restrict abortion, and the other half have passed measures to protect access.

The case is about one medicine, but it could be any medicine according to Dr. Banks, who helped sign the brief in the case.

She explained that the FDA process is expensive and not perfect, but that it’s predictable. She said that if there is a moral objection to medicine and friendly federal courts, that predictability goes out the window.

The uncertainty could affect investors and drug companies and “could put innovation for new drugs and much, much needed therapies for patients, not just in the United States, but globally, at fundamental risk,” Banks said.

The pharmaceutical industry is scared because of that. If this could happen with any other drug, what would stop people from doing it, since it’s been controversial and has a very, very low complication rate?

Legal scholars say that there’s an even bigger case that could affect everyone in the country. “You have, lurking in the background, the possibility that the Comstock Act is going to be reinvented as an abortion ban,” she says.

The Comstock Act is a 19th century law prohibiting the mailing of things for “indecent” or “immoral” use. The plaintiffs in this case use Comstock in one of their arguments, treating it as a straightforward statute and not a defunct law.

Mifepristone is not prescribed for women, nor is it prescribed for men? A lawsuit filed in February 2018 by the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine

Despite decades of scientific consensus on the drug’s safety record, the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine has alleged that mifepristone is dangerous to women and leads to emergency room visits. A 2021 study cited by the plaintiffs to back up their claims was retracted in February after an independent review found that its authors came to inaccurate conclusions.

Julie F. Kay is a reproductive rights lawyer and director of the Abortion Coalition for Telemedicine.

Former US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) commissioners, who are representing pharmaceutical companies in a Supreme Court case related to abortion, have argued that it could “affect the authority of federal agencies and the drug industry.” They claimed that the case could be used to challenge FDA approval of a rival’s drug. More than six in 10 abortions in 2023 were carried out via medication.